Learning to ask the right questions to get the appropriate answers

Precision Agriculture (PA) has many interpretations, but most people associate PA with Variable Rate Applications (or VR Technologies) and the terms are often used interchangeably. However, Precision Agriculture could be thought of as a more holistic set of “practices” or “tools” of which VRA is only one.

As a trainee PA consultant, I was often perplexed by the statement “PA asks more questions than it delivers answers”. Frankly, I didn’t always know how to respond. Experience has shown me that “PA forces us to ask questions that we needed to ask” and if we can’t answer the questions, then we are either asking the wrong questions or we don’t have the right data to give us confidence that we have the answer.

To elaborate, growing a great crop is about nailing that relationship between the plant, inputs, and its environment. Manipulating phenotypic traits or ensuring you provide adequate, available resources to give the plant the best chance to grow quickly, efficiently, and with enough yield allows for optimal profitability. However, this is rarely considered when I ask farmers why they want to implement VRA. The response is often “to reduce the fertiliser bill”. I invariably have a standard response: experience has shown me that in most instances, we are “robbing Peter to pay Paul” and the bill ends up the same. So I ask the question again and am often left hearing crickets.

Let’s consider that some areas yield better than others, sometimes consistently, sometimes yield varies. Variability in yield is almost always due to changes in production capacity. Each production capacity zone will probably have a range of different characteristics that results in some crops yielding consistently high, consistently low, or are consistently inconsistent.

So maybe a more appropriate question should be asked, “How do I tailor the inputs to productive capacity?”.

So, we can use PA to:

- Identify variability – more specifically crop yield variability that is attributed to some inherent quality of the landscape and or soil, and

- Respond to variability – eliminate, ameliorate, or manage identified variations in the growing environment.

Using a stepped approach to our appropriate question ‘How do I tailor the inputs to productive capacity?’, we now have some clear actions.

Identify variability

Create base ‘production zones’ that are characterised by changes in production.

Yield data is the only quantitative measure of spatial crop variability. Taking a yield map, having it processed and displaying the data can help identify where and how much yield is being lost by something.

The number of years of data required is determined by your level of confidence in the data. For many people they want to see years of stability in variation, for other people one yield map captures the expected variability perfectly.

Remember, the only aim here is to capture variability to guide the next few questions. This is not necessarily the only data you will use to make future decisions on.

Use these ‘zones’ only to identify what is causing the variability

Accurately identify what soil, landscape, or combination of these is impacting productivity.

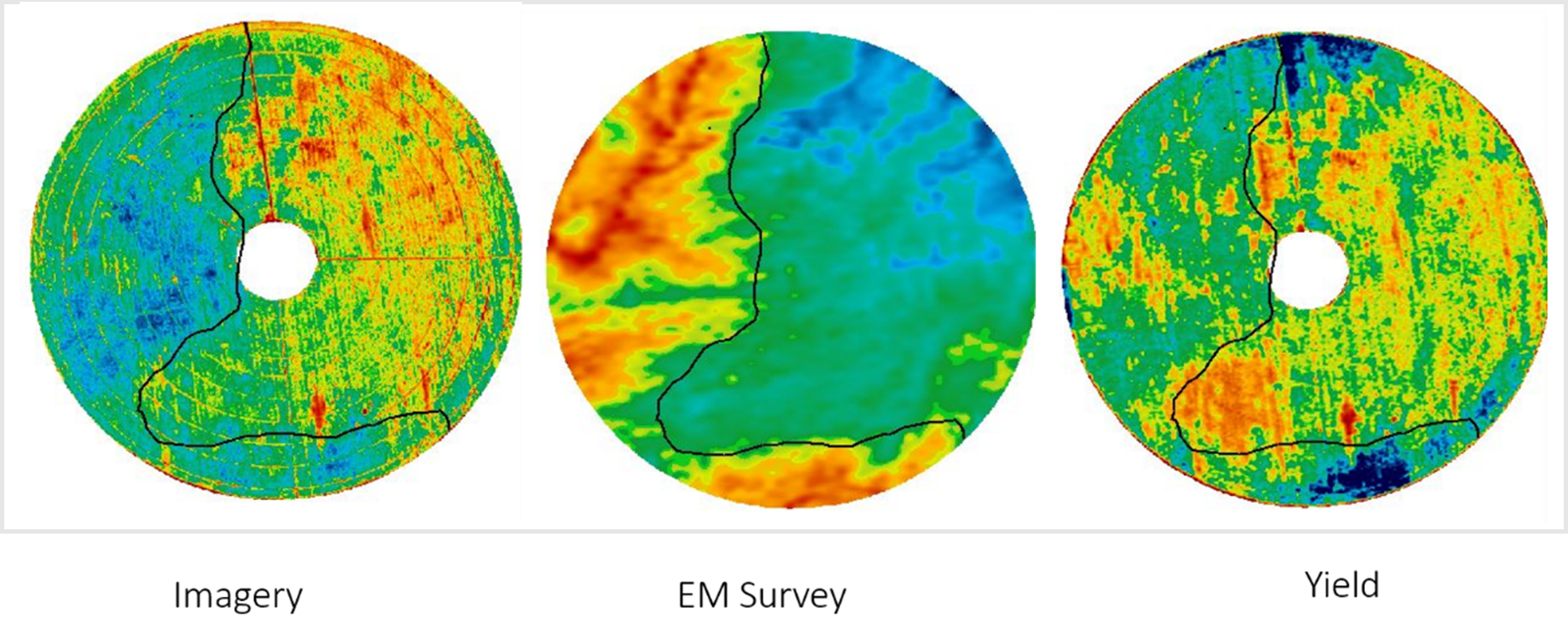

This can start with just looking at the range of different yields and directing soil sampling. It could also start with using yield and comparing it to something more stable like a layer that captures changes in soil type. Examples could include an EM Map, pH map or radio metrics. Alternatively, using something available like a fuel use map (from a seeding application) or elevation data could also be of benefit.

Measure the impact of that variability

How much yield am I losing? What circumstances change how much yield I lose?

Is soil type change driving yield variability – YES

Is this relationship expected – NO

In this instance we are looking at how much yield is influenced by changing clay content or levels of salt that are present the soil. The EM survey adequately highlights changes in soil type (red and black soil) and subsequent changes in clay content and water holding capacity.

However, in this instance the increasing clay content and water holding capacity is having the opposite effect on yield.

What other information do we need? Through some targeted soil testing using the EM as a means to guide the sampling by “zone”, we were able to identify significant levels of salt within the soil profile.

What is the most appropriate response to managing variability?

Change something: Can I enhance and alter the impact on yield? Is there a clear and obvious cost benefit?

Change something: Can I eliminate the impact of the characteristic/s?

Live with it: “It is what it is!”, the goal is now to maximise profitability.

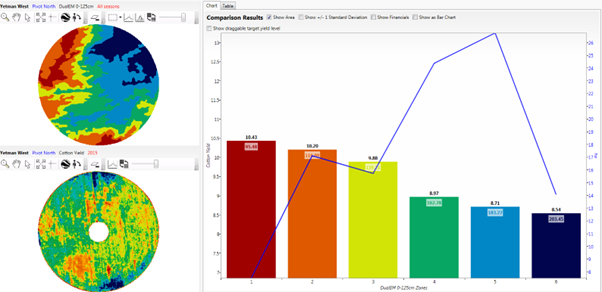

Managing variability is the logical last step, but often the initial due diligence or investigation is skipped and we can go down the incorrect path of management. Looking at a Yield X Soil relationship, it is easy to determine what soils impact yield the most and how many hectares (the blue line) are affected. Some key trends to look for are which soil do you have the most of? Some simple generalisations are; if the majority soil type is the highest yielding, then you are managing the field as well as possible. This helps answer the question of, is there a significant benefit to changing what we do now?.

Using the above example, there is a yield difference of 2 bales/ha. At $600/bale, that is a significant loss of profit. Additionally, this is an irrigated crop and the majority soil type (as indicated by the EM survey) is the light blue (see dark blue line on the graph).

Before altering N or water on the crop, the normal approach to VRA is we need to find a way to determine if N or H2O are indeed the limiting factor or if they are being underutilised and if so why. It often helps if as many people as possible can be part of the conversation. This includes your agronomist who knows just as much about your fields as you do. With the presence of salt in the profile, there is an option for fine tune crop management to compensate for reduced water holding capacity.

Author | Brooke Sauer, IntellectAg